Archaeologically excavated viking burials are rare in Britian, but the opportunity at Cumwhitton to examine not just one but six under modern excavation conditions was internationally significant. A close working relationship with the metal detectorists who discovered the site helped to uncovered the whole cemetery.

The acidic soil conditions meant that preservation was poor, but innovative use of soil block lifting and laboratory excavation, as well as scientific analyses, allowed mineralised organic remains to be identified in the corrosion products and the objects and burial rites to be reconstructed. This resulted in a fascinating glimpse of the funerals of these people, which took place over a thousand years ago.

Treasures in the sand

The discovery

In March 2004, Peter Adams of the Kendal Metal Detecting Club found what appeared to be a brooch in the ploughsoil on farmland on the edge of Cumwhitton, Cumbria. This was reported to the Portable Antiquities Scheme, which, with help from the late Ben Edwards, identified it as a Viking double-shelled brooch. These were worn in pairs, so Peter and his friend George Robinson returned to the site and sure enough they found another one!

Finding two together suggested that this might have been the site of a burial, so Oxford Archaeology was commissioned to carry out an evaluation which established that this was indeed the site of a grave. Such graves have traditionally been identified as those of Scandinavian women.

We worked with Peter and George during the evaluation, and they found fragments of many other objects in the surrounding ploughsoil. Whilst some of these could have come from this grave it was highly unlikely that all of them could, which raised the possibility that there could be a cemetery on the site. Historic England therefore funded a full excavation of the field, particularly given the threat to the site from ploughing.

In total we discovered six Viking burials dating to the first half of the tenth century (AD 900-950). Any furnished graves of this period are rare in Western Europe in general: only about 30 have been excavated in England, mostly in the North West, and mainly recorded by antiquarians in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Cemeteries are even rarer. Because of the acidic soil, the bodies did not survive and were only visible as shadows in the sand. The objects that accompanied them, however, opened a fascinating window on tenth-century Cumbria and the people who had settled in the area.

This discovery is of immense significance for our understanding of the early medieval period in the north west of England. To date the Viking burials that have been identified in the North West appear to be of locally important individuals who probably represent early generations of settlers to the region.

The graves

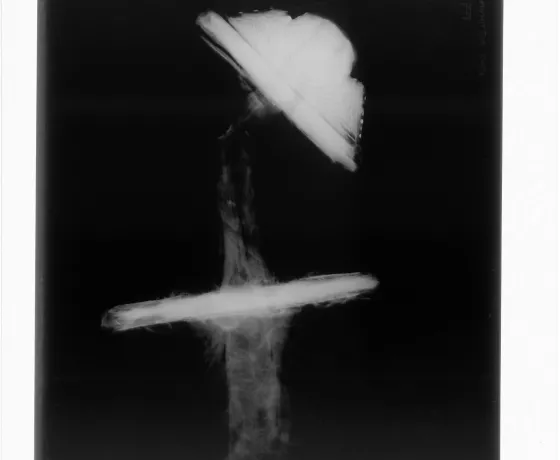

The first grave was aligned east/west and contained a small fragment of skull, which confirmed that the head was at the western end. The remains of a wooden box with iron fittings was found at the foot of the grave, containing a series of objects including shears, needles, a spindle whorls and a blue glass linen smoother. The corrosion products on the metal objects allowed us to identify that the box was made of field maple, and both contained and was surrounded by textiles. The corrosion products on the brooches contained larvae of insects which suggests that the body had lain in state for some time before burial, and was clearly dressed in a strap dress, the traditional attire of Scandinavian women, identified from mineralised cloth straps within the brooches.

The other graves were also orientated roughly east/west and were clustered together some 10 metres to the north/east of the first grave. They seemed to form two rows, suggesting that they were not buried at the same time. The eastern row contained a central burial which had a semi-circular ditch around it, probably dug to create a small mound over it, this grave contained a particularly find collection of grave goods.

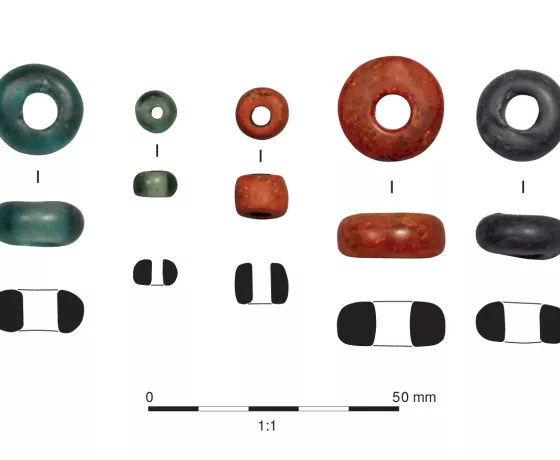

The range of finds was extensive, amongst which were four swords, multiple spearheads, an axe, a shield boss, spurs, drinking horns, beads, belt buckles, ringed-pins, knives, and a chain and hook presumably from a cauldron. These clearly demonstrated that the bodies were buried wearing clothes and were accompanied by objects that were both significant and symbolic.

The objects from all the graves came from many different cultures, showing affinities to Scandinavia, Western Scotland, Ireland, and Northern England. These may have been a single family group perhaps of only two generations, perhaps owning land around Cumwhitton. Why no other people were buried here is a mystery, although the amount of tenth- and eleventh-century sculpture with Scandinavian motifs in Cumbrian churches, including Cumwhitton, suggests successive generations converted to Christianity.

.jpg.webp?itok=ht1vnB0D)

Learn more about Cumwhitton and Vikings