What is it?

The word ‘archaeology’ conjures up many images, often involving muddy trenches, hunting for treasure, and digging up bones. As a buildings archaeologist, the work we do is very, very different and doesn’t usually involve digging holes in the ground.

The term “Buildings Archaeology” can cover different types of projects, but it is essentially investigating historic buildings to learn more of their history and past use. The broad aims are therefore similar to those of conventional field archaeology, and it does employ some of the same techniques, but there are also important differences. Most obviously buildings archaeology normally involves studying entire buildings rather than merely their buried foundations, and the approach can therefore be more broad brush.

Investigating historic buildings has a long tradition as an amateur pursuit including Georgian gentlemen studying classical ruins on the Grand Tour. However, in recent decades, in the wake of new planning guidance (initially Planning Policy Guidance 15 and then Planning Policy Statement 5), buildings archaeology has emerged as a distinct discipline within developer-led archaeology.

Some projects comprise the recording of simple, single-phase buildings, whereas others involve the lengthy analysis of complicated ‘archaeological’ evidence like constructional phases, evidence of repair, blocked openings, former doorways, and truncated structures.

Most of the buildings that we record are listed and have a clearly defined heritage significance, but many structures are unlisted, albeit with some local interest; sometimes they are 20th century in date, occasionally even from within living memory.

When is it done and who for?

Similarly to the wider field of developer-led archaeology most of our work fits into the planning system, either being requested by a local authority’s Conservation Officer as a condition of planning approval or as a heritage assessment submitted to support the consideration of a planning application.

Different levels of recording are specified and can span from little more than a small number of rapid photographs and a few notes to detailed measured drawings that require several days. This is the type of work that we have been doing since 1999 at the Royal Arsenal in Woolwich, as part of its ongoing redevelopment.

Numerous types of heritage assessment are undertaken, usually aimed at establishing the heritage significance of a building and the potential impact of a proposed development. Other types of historic building projects that we undertake include Conservation Plans or Conservation Statements which are sometimes commissioned for particularly important historic buildings, like Osbourne House and Tattershall and Carisbrooke Castles, just to mention some of the iconic locations where OA had worked.

Oxford Archaeology started undertaking Buildings Archaeology in the 1990s and the Buildings Archaeology Department, led by Julian Munby, was among the pioneers in this new area. We are a small (but important) cog within the overall wheel of the company.

We undertake buildings projects for a range of clients including heritage bodies (eg National Trust), private homeowners, Oxford colleges, major housebuilders, local authorities and construction companies. We’ve also undertaken work as part of major infrastructure projects such as both HS1 in the 1990s and HS2 more recently.

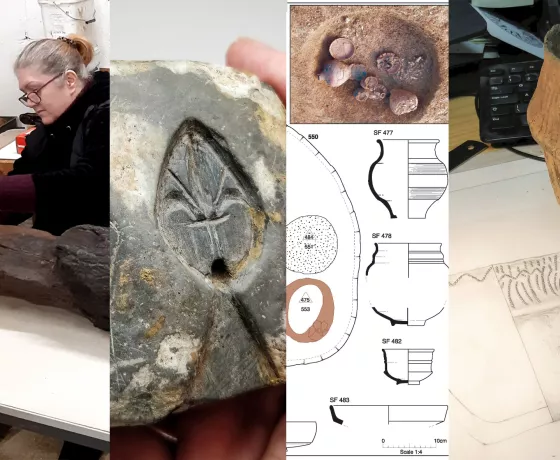

What do we actually do?

Sometimes the sitework is entirely undertaken before the start of demolition. On other occasions it also includes a watching brief phase when further recording is carried out during the strip out or demolition to record previously obscured elements of the building.

Every project also includes some historical research, as a minimum a study of old maps available on the internet but usually also including a visit to the local record office or other archives.

The extent to which historic maps can greatly help in historic buildings work is perhaps one of the main differences with most conventional field archaeology. Frequently mid-19th century maps can show in some detail the former layout of a building complex being recorded and can explain puzzling features which are not explicable from the physical evidence.

Things like census data can help show the social status of the house, the number of servants and the trades of the occupants. In addition, census data can help ‘bring to life’ building reports (which can sometimes be somewhat unexciting) by providing the names of families who once lived in the buildings.

With building recording projects, (ie those undertaken to meet a planning condition) the reports are then lodged in the Historic Environment Record (HER) and a project archive is lodged with an agreed museum or archiving body (eg ADS).

The career of a Buildings Archaeologist is certainly varied and often interesting or fun. It can involve visiting Grade I listed palaces or country houses but sometimes the most exciting sites are derelict buildings with peeling paint and ivy poking through windows. Ruined buildings can have a romance or sense of excitement that can be lost when or if the building is subsequently converted. It is often the hidden areas of buildings which are the most interesting, areas which are not intended to be seen such as roof spaces with witch’s marks or graffiti to the trusses.

Visting some buildings can be truly awe inspiring and memorable, particularly industrial structures such as derelict railway sheds, vast erecting workshops or the interiors of gasholders. Other buildings such as former prisons can be unnerving while former hospitals or asylums can be deeply moving. Air raid shelters or pillboxes can also be poignant, particularly if they retain any graffiti.

The artefacts that are sometimes found always provide a small glimpse into the lives of the people who lived there or worked there, even when they only date to the 1970s or 1980s. One of the more unusual artefacts found and recorded was a sausage found high up a wall at Stowe School, stuck on top of a section of coving and presumably thrown by a school pupil.

Paint stratigraphies or layers of wallpaper (sometimes many layers deep) can highlight changing decorative tastes and give a tangible illustration of the passage of time. It can be striking to realise that a room which today has plain white walls used to be painted a dark brown colour or had heavy decorative wallpaper.

One of the exciting things about working in buildings archaeology is the huge variety of projects that we work on, from castles and churches to factories and army barracks. And sites that show us the everyday lives of normal people, like farmhouses and old pubs. In upcoming posts we will be discussing some of our favourite examples of these in more detail.

Other posts in this collection

Explore with us all the different disciplines and specialist areas that make up our archaeological practice.